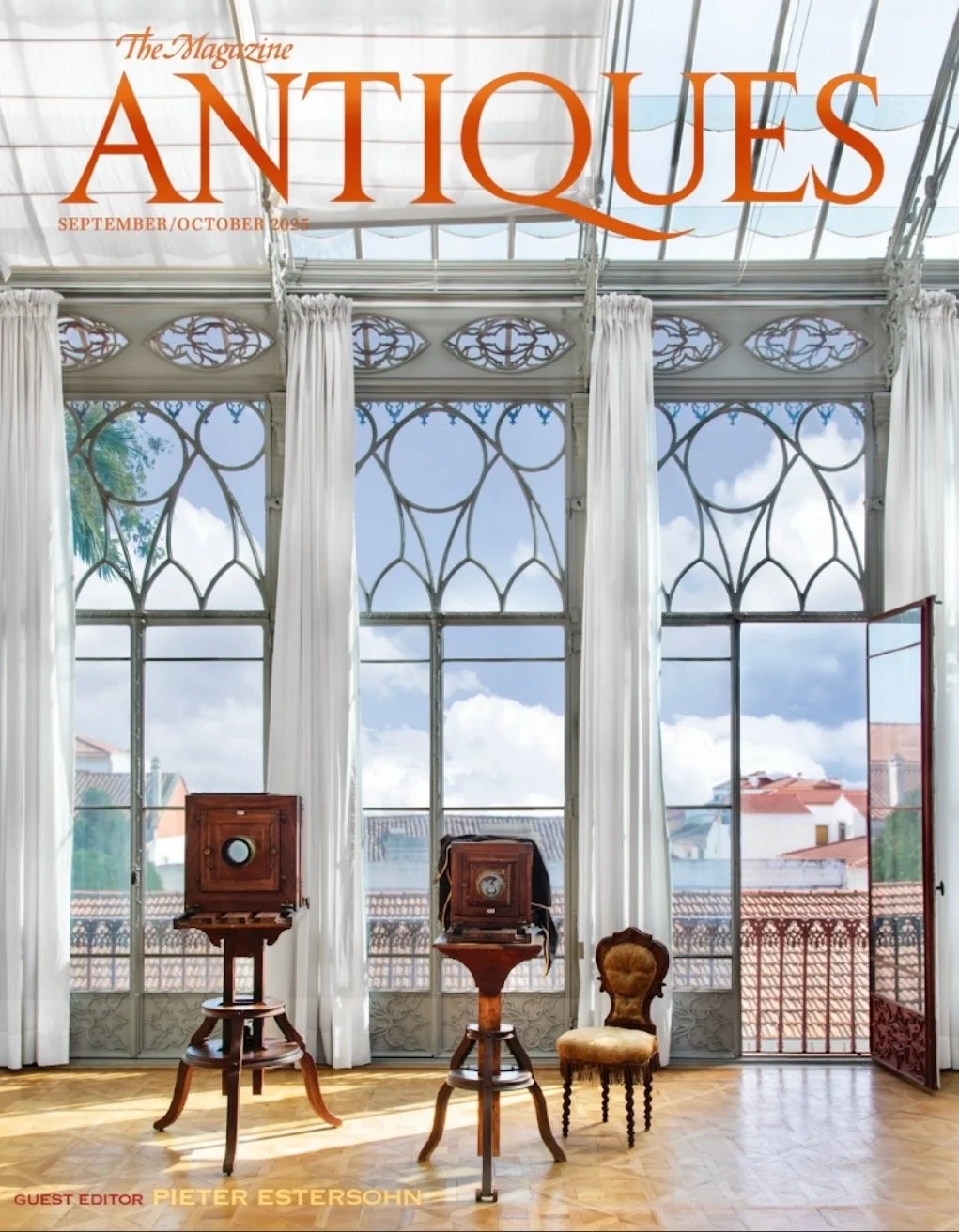

Jacopo Etro’s Puglian Palazzo

TEXT VERSION (SAME ARTICLE) BELOW, WITH PIETER ESTERSOHN’S MARVELOUS IMAGES:

Jacopo Etro’s summer retreat in Puglia, Italy, stands as an ode to the collector’s impulse: the thrill of discovery, a reverence for decay, and the restless eye that turns a house into a captivating tale. Built during the seventeenth century in the medieval town of Matino by a prosperous olive farmer, Palazzo Giannelli was enlarged and completed around 1870. The two-story palazzo had stood empty for sixty years when he found it in 2012.

“Time stood still,” says the sixty-two-year-old eldest scion of the eponymous Milanese fashion dynasty known for its luxurious profusion of paisley, founded by his father in 1968. The house’s frescoed walls and soaring eighteen-foot vaulted ceilings—in gorgeous shades of violet, pink, and ocher—were faded but intact. “I wanted to keep it as it was, even the shadows of the furniture on the walls,” he adds. “My architect told me, ‘You’re crazy!’”

A chandelier made from jagged shards of broken glass by Deborah Thomas (1936–) hangs above a nineteenth-century bench in the formal sitting room of Jacopo Etro’s palazzo in Puglia, Italy. All photographs by Pieter Estersohn.

Raised in a family that revered the visual world, he was exposed to art from the age of six when his parents, Gerolamo and Roberta Etro, an erstwhile textile dealer and an antiquarian, began taking him and his three siblings around the world, visiting museums in Paris, Rome, Venice, Florence, Mexico, Cambodia and throughout Asia. “We were very lucky to be brought up in such a family,” he says.

His passion for collecting began at eighteen with anatomical drawings he found in flea markets and has blossomed into a rich, genre-defying assemblage of the rare, the beautiful, and the bizarre. Unlike his parents—collectors of museum-quality Asian art, Old Masters, ancient marble sculptures, and modern Italian art—he is drawn not to provenance but provocation. “I like things that give me a strong reaction,” he says. “I’m not chained to names. I collect for pleasure.”

The French and Italian glazed masks from the 1940s and 50s on the far wall of another sitting room are grotesque and devilish, in keeping with Etro’s delight in the ghoulish.

He hankers for objects that are challenging to find and eschews pious depictions of Madonnas and heaven, which are ubiquitous in Puglia. “I’m not interested in paradise,” he says. “None of my friends are there. I prefer devils to saints,” he adds with a grin. “Devils are harder to find.”

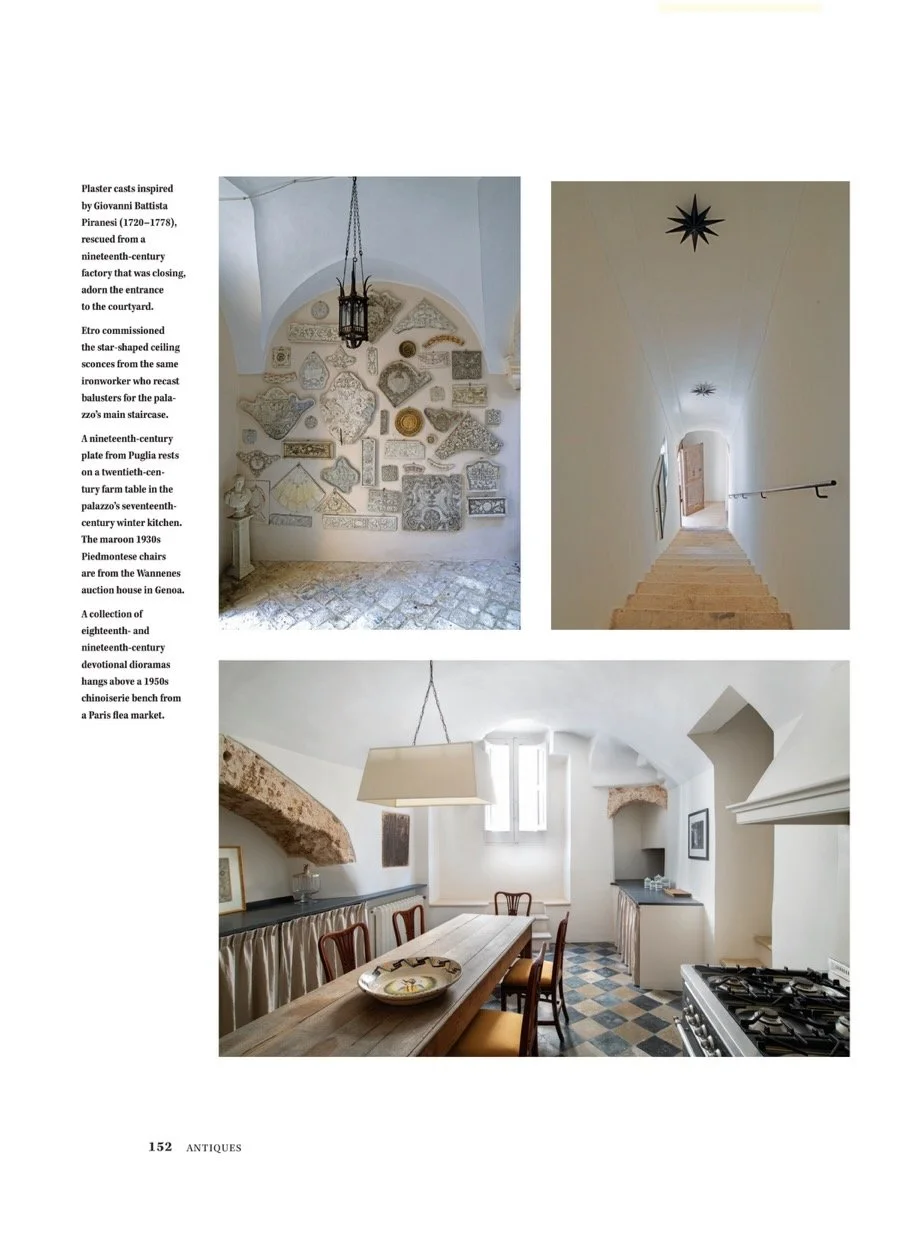

That sly wit and irreverence pervade the sixty-five-hundred-square-foot palazzo, where the juxtapositions are never predictable. Visitors enter the house via a courtyard festooned with classical Piranesi-inspired plaster casts. Inside, an eccentric collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century devotional dioramas—reliquaries and other shrines made from human bones and shells by Italian nuns and wives awaiting lost sailors—flank a 1950s chinoiserie bench painted a vivid orange red, from a Paris flea market.

The palazzo’s main staircase overlooks the entrance courtyard. Some of the nineteenth-century iron balusters were broken or missing and had to be recast.

The formal rooms are no less theatrical. Skulls leer from dark seventeenth- and nineteenth-century memento mori paintings in a sitting room with a nineteenth-century bench upholstered with crimson velvet and a baroque–at-first-glance chandelier made from jagged shards of broken glass by Deborah Thomas, a contemporary British artist whose sought-after illuminations encompass luxury and salvage. Another sitting room—there are four—displays a collection of nineteenth-century marble specimens with a 1960s painting of flying fish by Aldo Mondino, and a cozy armchair upholstered in a yellow Etro fabric with a riot of Chinese monkeys that he designed twenty years ago.

Skulls leer from seventeenth- and nineteenth-century memento mori paintings in the formal sitting room. The unsigned triptych of photographs of the sea, right, was found at a Paris flea market. A french chair in the Directoire style, left, is upholstered with a striped Etro fabric. In the corner, a nineteenth-century neo-Pompeian wooden structure conceals a pellet stove.

A nineteenth-century screen, with Zuber panels of Vesuvius erupting, is flanked by a pair of theatrical encrusted with shells. The chairs are Napoleon III.

“I like to mix things from different periods,” he says. “Ancient, medieval, 1950s, Napoleon III, and also kitsch. Kitsch makes me smile.” The dining room glows with a tall nineteenth-century screen with Zuber panels of Vesuvius erupting, flanked by a pair of theatrical busts encrusted with shells that remind him of Tony Duquette, the Hollywood costumer and decorator known for his outré flair. “I find them very funny,” he says. Similarly, an 1874 Orientalist painting by Paul-Désiré Trouillebert, Harem Servant Girl, with a bejeweled naked torso, lounges over the bidet in a guest bathroom, opposite a late Roman mosaic, circa 300 CE, of a dolphin impaled by Neptune’s trident.

A dolphin impaled by Neptune’s trident writhes above the tun in a guest bathroom in a Roman mosaic of c. 300 CE.

These felicitous, unexpected encounters are a radical departure from the purist interiors he inhabited as a child. His parents’ place in Paris was an original 1928 art deco apartment with important Ruhlmann furniture. Karl Lagerfeld and many of their friends, he recalls, were avid collectors of art deco during the 1970s. He now owns the apartment, which overlooks the Jardins du Luxembourg, and has chosen to maintain that sleek aesthetic in Paris, the city that spawned art deco with the influential 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. During his formative years Etro also spent time at his great-grandparents’ seventeenth-century country house. “It was very dark, very heavy—something I don’t like anymore,” he says. “Not my style.” But he’s kept an heirloom from that ancestral house—a seventeenth-century portrait of Saint Jerome, painted on wood, which hangs above a marble console in Puglia.

A seventeenth-century portrait of Saint Jerome from Etro’s great-grandparents’ country house hangs above a marble console, facing a nineteenth-century glazed maiolica chair, traditionally relegated to outdoor terraces. The neoclassical plaster casts date from the nineteenth century.

His white-walled apartment in Milan contains an extensive library devoted to his gleeful fascination with snakes, monsters, and skeletons, along with some historic accoutrements of the dark arts. “The piece I’m most interested in is an eighteenth-century bell, engraved with demons, that was used in sorcery to summon the devil,” he says. He’s taken the precaution of removing the ringer. “Just in case,” he says. “Some people get scared in my house,” he continues. “They see all these skulls and evil things, but I really love them.”

No apparitions, saintly or sinister, have been reported in Etro’s Puglian idyll. A pair of Roman gladiators (nineteenth-century copies) grace a Neapolitan console table on the pink-frescoed landing at the top of the stairs, along with two rare eighteenth-century named portraits of actors from the Comédie Française. “They’re not in good condition, but I don’t care,” he says. “Quality is important, but these are unique.”

No apparitions, saintly or sinister, have been reported in Etro’s Puglian idyll. White marble nineteenth-century copies of Hellenic statues—the Borghese Gladiator by Agasias now in the Louvre (c. 100 BC) and a similarly chiseled playmate—grace a Roman console table on the pink-frescoed landing at the top of the stairs, hung with two rare eighteenth-century portraits of actors from the Comédie Française.

An eighteenth-century papier-mâché rhinoceros greets passersby in a tiled anteroom that connects the original seventeenth-century part of the house with the 1870 addition. “I call it the modern part of the house,” Etro jokes. Visible from the street, this second-floor room also contains four ebonized church pedestals—one in each corner—macabre sentinels adorned with crosses and skulls. “More skulls,” Etro says, cheerily. Another anteroom is dominated by a nineteenth-century pietra dura table with a swirling design whose gilded base features grotesque sea creatures that resemble writhing dolphins. Nearby, a tall hand-painted nineteenth-century cabinet is topped with a collection of Puglian peasant vases from the 1940s and ’50s.

Portraits of Saint Sebastian, the patron saint of athletes and archers, and Christianity’s first gay icon, adorn the walls of Etro’s bedroom, where an eighteenth-century wooden figure of an African man in the exoticist Blackamoor style—sold to him, somewhat unconvincingly, as a depiction of Shakespeare’s Othello—attends a Piedmontese chaise longue, strategically placed next to a hand-painted folding nineteenth-century French screen concealing a powerful air conditioner. “I don’t want to see them,” he says. “But you need air conditioning in Puglia. I’m there in June, July, and August.”

Portraits of St. Sebastian, the patron saint of athletes and archers, hang in Etro’s bedroom.

Eighteenth and nineteenth-century gouaches and paintings of Vesuvius erupting—staples of the Grand Tour—adorn the walls of his dressing room, along with a contemporary sculpture by Ignazio Mortellaro—a ghostly vertical panel of gray and white painted over traces of red wax, which reminds Etro of a roiling Vesuvius. The fiery theme is echoed by a 1965 vibrant red-lacquered chest of drawers by Carlo de Carli and by the crimson leather surface of an ebonized Napoleon III table, which displays a nineteenth-century brass Hindu mukhalinga, a reliquary penis shrine, from Karnataka, India. “They used to put the male organ inside,” Etro explains. (This one is currently unoccupied.)

A nineteenth-century brass Hindu mukhalinga (reliquary penis shrine) adorns a Napoleon III table in Etro’s dressing room.

An eighteenth-century portrait of a Spanish sculptor in a formal blue frock coat, with a chiseled male nude in the background, hangs on another wall in the dressing room, above a nineteenth-century French campaign bed. “I wanted a masculine room, and a masculine portrait looking at me when I get dressed,” Etro says. “It’s nobody famous,” he says of the portrait, “but I found it interesting and charming. A man with a nice face who enjoys art.”

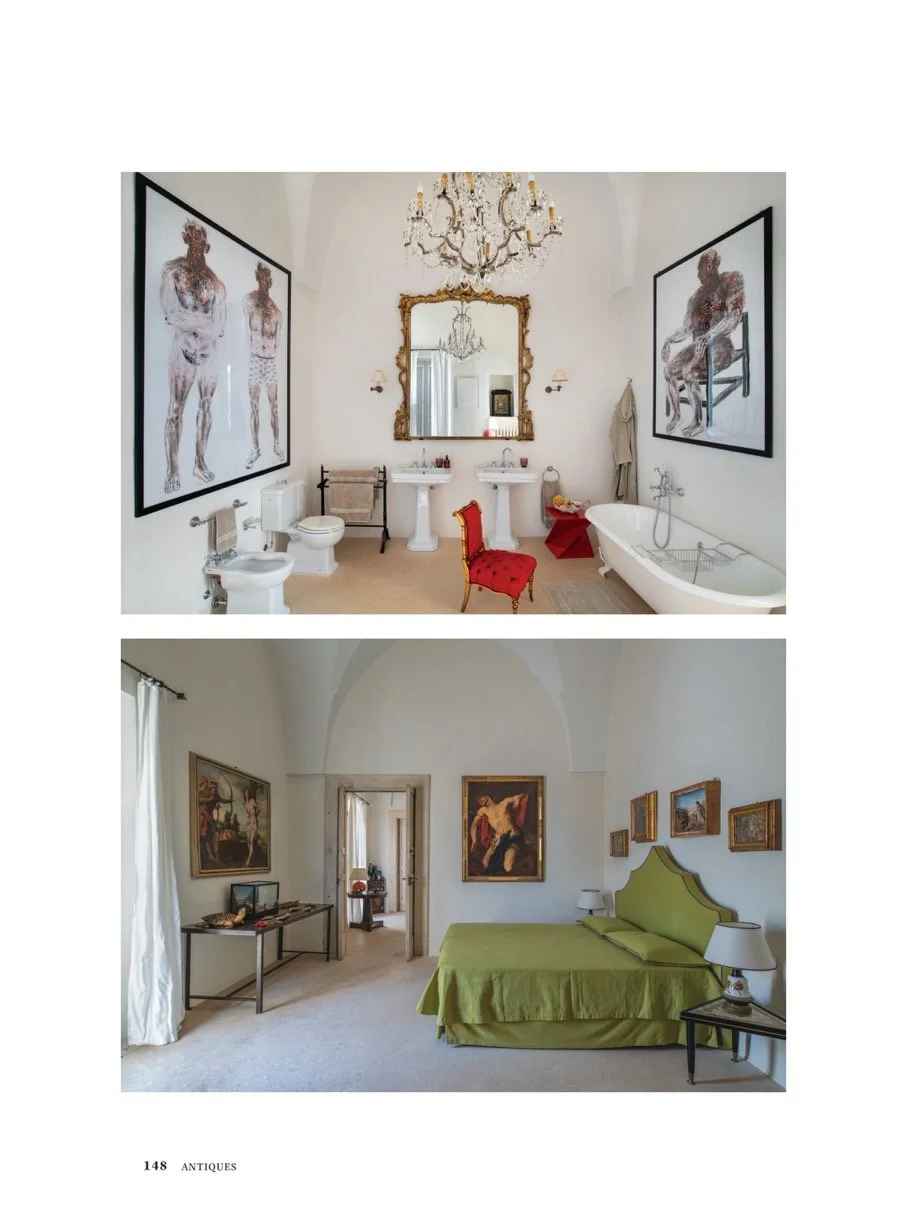

A Napoleon III chair upholstered in carmine red and a nineteenth-century chandelier are soigné companions for two large contemporary artworks of male figures in Etro’s bathroom by Salifou Lindou, a Cameroon-based artist, that he found at the I-54 Contemporary African Art Fair held every year in London during Frieze. Lindou’s portrait of a naked Black man sitting in a chair, which hangs above the bathtub, reminded Etro of Velázquez’s iconic seated portrait of Pope Innocent X at the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome. “I love things that remind you of the past, but aren’t obvious,” he says.

A Napoleon III chair upholstered in carmine red and a nineteenth-century chandelier are soigné companions. for two large contemporary drawings of male figures by Salifou Lindou (1965–) in Etro’s bathroom.

Second Empire chairs from the 1870s can be found throughout the house. “When I bought them twenty-five years ago the French couldn’t have cared less about Napoleon III,” he says. “I was crazy about them. They were decorative but inexpensive.”

A large nineteenth-century soleil mirror from a church in northern Italy hangs above the bed in a guestroom, casting a gilded glow over eight eighteenth-century prints of Charles Le Brun’s seventeenth-century Beastmen drawings, depicting animal heads alongside humans with eerily similar physiognomies. Beasts and men keep company with a wonky Victorian campaign bed on wheels and a tortoiseshell and mahogany bookshelf of a similar vintage. “The British used to make these Victorian low bookshelves which are comfortable,” Etro says. “It’s easy to grab a book, without reaching, and you can still decorate on top.”

A nineteenth-century soleil mirror from a church in northern Italy hangs in a guest room.

When the heat becomes excessive in summer, Etro and his husband, Alessandro Genduso, a Sicilian doctor from Palermo, head to Palazzo Giannelli’s rooftop terrace, which offers views of the Ionian Sea. “It’s the freshest place,” Etro says. “The idea of a garden in town seems wrong because it’s hot, but there’s a plunge pool and in the evening, you have breezes coming from the sea.”

The rooftop terrace has a plunge pool and views of the Ionian S

Reflecting on the pleasure of assembling so many disparate cherished objects under one roof, from the ancient to the contemporary, Etro laments the younger generation’s pervasive ignorance of history and the visual arts. “They only care about being on the phone and social networks,” he says. “It’s a pity, I think, to lose all this knowledge.”

“Preserving the past is important these days,” he continues. “Contemporary architecture is often so soulless. The good thing about Italy is that you can find ancient places and bring them back to life.” Another project is underway—a secluded house near the beach in Sicily with cactus and an orange grove. His Sicilian husband is leading the charge on that garden. “I know nothing about dry gardening,” Etro says. Their daughter, a precocious six-year-old with a knack for drawing snakes, is already showing signs of a fierce eye. “She has a great sense of color, and she loves going to museums. We’ve taken her to Rome and Venice.”

Etro is curiously unsentimental. Once a house is complete—once the story is told—he’s ready to let it go. “I’m not attached to things,” he says. “I might give the Puglia house away as a museum. But the house in Sicily, that’s a new chapter.”

CHRISTOPHER MASON, a journalist and editor, is the author of The Art of the Steal: Inside the Sotheby’s-Christie’s Auction Scandal. He also writes and performs funny musical toasts, roasts, and satirical songs.